Essays

Linseed Oil and Painting and The Yellowing of Paintings

The Prairie

The Artistic Dilemma

In 1987, the minimalist and abstract expressionist Agnes Martin delivered a talk to the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. During the conversation, she emphasized the importance of artists getting to know their true and unconditioned selves and creating culture rather than feeling like they are simply a part of an existing culture. She also stressed the idea of artists relying on their own minds for ideas and emphasized that artists don’t choose to be artists; they are compelled to follow their calling.

Fiction VS Non-Fiction

It helped me clarify some of my feelings about art, but I disagreed with her view that “the artist must give up non-fiction.” This belief was the foundation of art in the 20th century, and it was its weakness and strength. Art based on fiction and emotions in response to the real world runs the risk of simply imagining the pain of life, death, and the turmoil of the human experience. In other words, by hiding behind an illusion, the artist doesn’t offer hope or direction for humans to create a new world. Instead, the artist becomes a skillful doodler. This is the default outcome when the artist needs proper training in drawing, painting, or sculpting skills and has nothing meaningful to express.

The Connection of Art and Knowledge

Throughout history, periods of great technical skill and beauty in art have coincided with significant leaps in knowledge and technological advancement. As a result, art has been seen as a pursuit of perfection, allowing artists to express themselves freely and break away from traditional constraints. Art has the potential to offer new perspectives on our world and is created through a combination of observation, analysis, discovery, and inspiration.

However, the evolution of art has led to a loss of connection with its original purpose. The invention of the camera made some believe that artists were no longer necessary. This perception shifted with the promotion of “Art for Art’s Sake” by Oscar Wilde, which emphasized the intrinsic value of art. Previously, paintings played a crucial role in inspiring religious devotion by visually presenting biblical events for those who couldn’t read. Artists also recorded historical events, depicted people, and even delved into scientific exploration, as seen in the work of Leonardo Da Vinci. Art has evolved beyond simple emotional responses to encompass a range of subjects such as war, illness, beauty, and color. Movements like impressionism provided artists with more freedom, allowing them to express their emotions and create enigmatic, thought-provoking images.

Nevertheless, the skills of the old masters have diminished, and critics have lost the ability to evaluate art effectively. In present times, paintings often mimic photographs or are created from photographs with the intention of perplexing, mystifying, or shocking the viewer.

Art is not a pure replication of reality.

Real artistic pursuit is like walking along the ridge of a roof. You may slide down on the side that will take you into lifeless accuracy or slip down the other side with the result of meaningless lines and color. Undoubtedly, it is holding both simultaneously, which is the real challenge of the artist. Art is this challenge that is the gift that the artist can give to the world. To that end, it is this position that I have tried to hold on to, walking on the edge, not slipping down one side or the other. I hope you enjoy seeing my efforts to climb back to the ridgeline.

Venues have become big business, and the requirement that the artist produce a vast quantity to satisfy the galleries makes it nearly impossible to deliver both quality and quantity. This is also coupled with a lack of skills taught, which means critics and curators must have the knowledge to judge to the detriment of the artist and the public.

New Mediums a Loss or a Gain

Computer skills may provide a new means of expression to replace traditional tools like pencils and brushes. We can already see impressive results in movies and advertising. However, the expertise and organization needed to achieve these results mean that individual artists need help overcoming declining technical skills in traditional art forms such as drawing, painting, and sculpture. Plus, the distance between the artist and the end results may be too great and complex, with too many middlemen, programs, and applications to replace the solitary artist.

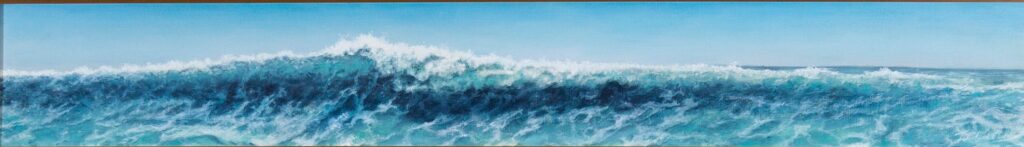

The Wave

Painting at the start of the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, the use of linseed oil revolutionized painting. Its superior qualities quickly replaced other mediums like tempera (made with egg yolk or egg white) and distemper (usually consisting of powdered chalk, lime, and size). Although fresco painting, which involves applying pigment to wet lime plaster, persisted to some extent, it could not match the versatility, durability, and flexibility of linseed oil.

The Introduction of Linseed Oil

In the annals of art, frame makers played a pivotal role in the transition from egg tempera to linseed oil. They utilized linseed oil as a wood finish and a paint binder for the carved and gilded altarpieces, making the task of painting scenes for altarpieces much more efficient than carving. This shift in technique, facilitated by the high demand for portable altars, led to the predominance of painted religious scenes. Simultaneously, the introduction of linseed oil, with its ability to enable more realistic painting than egg tempera, swiftly replaced the latter on the panels.

Stained glass artists, with their unique perspective and skills, provided invaluable insight into oil painting techniques. They shared their knowledge on how to use oils to create thin glazes and painted grisailles designs, thereby advancing the art of oil painting.

The Techniques From Stained Glass

It is no coincidence that the first oil paintings resemble stained glass windows. The oils or water in stained glass evaporated or fired off when fusing the pigments into the glass. The artist would then repaint the glass and refired to add depth to shadow and color, often multiple times. The artist, painting on panels, incorporated the techniques of layering and drying (not firing) the painting using linseed oil. With linseed oil, the panels dried in the air, sometimes with exposure to the sun. This method gave depth to the panel, which was impossible with egg tempera.

Another technique the stained glass artist used was delicately erasing pigment before firing the glass. This erasing perfected shadows. Something almost impossible with purely applied pigment with a brush. This erasing or removing pigment before it dried was also transferred to oil painting.

Problems To Avoid

When painting on glass, the water-based pigment often beads up or treacles. The solution is to wash and de-grease the glass with soap. Similarly, when working with linseed oil, the problem is similar, and beading or treacling can occur. Linseed oil forms a tough and waterproof surface when dry. Unlike most oils, it goes through a chemical reaction and changes into linoxin rather than drying. This impervious quality of linoxin can cause subsequent paint not to adhere correctly to the underlying layer. It becomes a problem only when painting wet paint over dry paint. The thickness of a pigment mixed with linseed oil causes it to appear to adhere to the surface, but it may pull away from the underlayer, leading to a separation months or years later. Fixing these specific passages of a painting can be difficult, if not impossible.

The Reason For The Problem

When made, the pigments absorb different quantities of oil. This inconsistent oiliness causes some colors to be oilier than others and less able to bind with subsequent layers of paint. Different pigments, when dry, can appear shiny or flat. The flat colors have “sunk” and seem ready to accept another coat of paint but may be prone to resist subsequent paint layers.

The sollution

It is possible to tell where the paint applied will hold once it has cured by testing the surface. This testing done by spreading or brushing on a small amount of pure linseed oil on the painting will show if the next coat of paint will adhere properly. If the oil spreads smoothly, it usually means no problems applying a subsequent coat of paint. If the oil treacles or beads up, there will probably be a problem with the paint not sticking correctly, and cracking may result. Test each color and passage to avoid problems.

The problem can be corrected by using an isolation varnish or painting medium. However, this method means a loss of integrity caused by varnish inside a painting, stickiness, discoloration, instability, and cloudiness caused by moisture. I prefer treating the surface with paint thinner, soap, or some other mild degreaser, even linseed oil, messaged into the surface until it is stable.

A More Detailed View of the Above Article

LINSEED OIL:

Before the Renaissance, painting involved applying a pigment to a surface using a vehicle, a liquid, to spread the pigment and glue to hold it to the canvas.

The Renaissance introduced artists to flaxseed oil, also known as linseed oil, which was both vehicle and glue. Overnight, linseed oil replaced other mediums as the choice for painters. Other popular mediums of the time, such as tempera (using egg yolk or egg white), distemper (usually made from powdered chalk), lime, and size(?), almost disappeared. Mixing pigments—casein or milk solids, blood, wax—were continued only as furniture or wall paint. Continuing at a diminished level was Fresco painting, applying pigments mixed with water to a wet lime plaster.

Only gums/size and pigment mixtures continued in watercolors, gouache, and tempera painting (poster paints). These methods could not compete with linseed oil’s versatility, durability, and flexibility in painting pictures.

THE REVOLUTION

The change was so sudden that artists who painted in egg tempera, the most common form of the time, and balked at the new trend were forgotten in their lifetimes. Botticelli (Sandro Botticelli: Life and work. 1445 to 1510) was a genius with egg tempera but became abruptly passé. Unfortunately, Botticelli was also a follower of Savonarola Girolamo Savonarola and almost stopped painting except for religious work. He saw the destruction of many of his paintings. By the time Savonarola was executed, Botticelli was 53 and was out of style. He was eclipsed by artists who used linseed oil: Andrea del Sarto, Titian, Michelangelo, DaVinci, and many others. Although Botticelli made a few attempts at painting in oil, he never made the change. He died in obscurity and was forgotten for 400 years. He exemplified the sweeping change that Linseed had in painting. Egg tempera’s main problem was that it dried too quickly. It gave the artist little flexibility and made it almost impossible to paint glazes or have any transparency possible with oil.

OPENING THE DOORS TO/FROM OTHER MEDIUMS

Because linseed oil had been used in other artistic mediums, the painter had access to these experiences and techniques.

Medieval stained glass artists and wood finishers had used oils, specifically linseed oil, for hundreds if not thousands of years. Woodworkers of the time often created engaged frames (frames built as part of a panel to what?) that were then painted or gilded, sometimes using linseed oil and pigment to finish the wood. It was a natural progression from woodworkers’ polychrome altarpieces to the portable painted panels. Originally in the commonly used egg tempera, the wood craftsmen incorporated linseed oil into paintings that replaced the carved and gilded panels.

It is not a coincidence that the first oil paintings resemble stained glass windows. Stained glass artists used mediums such as lavender or walnut oil only as vehicles to spread the glass pigments. They most often used water and gum Arabic for glazes that were later fired into the glass. These artists opened the door to a method for spreading color and line that fits well with linseed oil’s characteristics.

The oils in glass work evaporated or were burnt off when the pieces were fired, and the pigments were fused to the glass. The steps would be repeated, and the glass would then be repainted and refired—sometimes three or four times—to add depth to shadow and color. The fine artist could now incorporate these techniques of painting with linseed oil. Instead of firing glass, the wood panels were left to dry. Each time the oil dried, another layer could be added with additional pigment to create depth and complexity in the passage.

In painting on glass, a problem is encountered when water-based paint beads up or treacles with glass. The solution is to wash the glass with soap. When working with a painting, the problem is more complex; the same issue of beading or treacling can occur. Linseed oil has a tough and waterproof surface when dry. This quality of linoxin can cause subsequent paint not to adhere to the previous layer. It causes a problem only when painting wet on dry, not wet on wet—and not always. The problem is related to the fact that different color pigments absorb various quantities of oil when made, causing some colors to be more oily than others and resist adhering. Some pigments are dry and shiny, others flat. The colors that dry flat are said to have “sunk” and would appear to accept another coat of paint readily. These sunken colors are often the most prone to resist subsequent layers of paint. Paint applied directly from the tube may seem to hold but has not, once cured.

Wood refinishers or painters who work on woodwork, such as door frames or molding, solve the problem by sanding or using a primer. Sanding is rarely an option for the fine artist. Using a medium or retouch varnish solves this problem. It allows the surface of a painting to accept another coat evenly but at a cost.

EVERY COLOR IS DIFFERENT

The ease of assurance that paint will adhere to this method is the same thing that makes the painting vulnerable to clouding or discoloration. The medium or varnish can also cause the painting to become sticky, making it challenging to apply a smooth coat of paint or a glaze without showing brush strokes. The problem can be solved without medium or varnish. To verify that the painting will take a coat of paint, spread a minor brush stroke of linseed oil on the dry painting. If it stays in place and does not bead or treacle, it is safe to assume the next coat of paint will hold. It is important to remember that this has to be done for each color, as each color will behave independently. If you see the oil treacling, address the problem by making sure that the painting is dry before you proceed by washing the surface of the painting with a coat of paint thinner. This will lightly etch the surface, similar to a light sanding. If the painting is dry, there will be negligible damage to the surface. Odorless paint thinners do not work well; they are also poisonous; you can’t tell you are being poisoned. Do this step with good ventilation or outside. It is best to test the painting again to verify that the oil stays in place and does not still have treacle or beads. The painting is ready once the oil does not bead anywhere on the surface. This procedure can be done with linseed oil if you don’t want to use paint thinner. It takes more time, but it also works, especially if the last coat of paint has a very thin glaze and is fragile.

MEET THE BASICS OF LINSEED OIL / SOME “GOTCHAS”

Linseed oil, also called flaxseed oil, is sold as a tonic for consumption. The quality sold for painting should not be consumed as it is not manufactured to be edible. It is applied with a brush but will bead up or treacle. If you continue to rub the linseed oil onto the surface, it will gradually form a continuous oil film. It works faster with warm or heated hands to help soften the surface. It may take five minutes.

Additionally, notice some colors take much longer. The oil is not a problem for your skin and can be used as a glove to protect your skin when painting. This makes it much easier to clean your hands later. Removing all the excess oil once it forms a continuous sheet and before you start to paint is important. It you want to paint wet on dry, paper towels work well. Use a cotton rag if you like painting with the feeling of wet on wet. Knitted cotton from T-shirts works best folded into a small square. FOLD IT BECAUSE … (don’t use a paper towel) If you don’t unfold the cloth, it will absorb only the excess oil and leave a film that allows the paint to flow smoothly without streaking, dripping, or running. You can use the paint directly from the tube, which will adhere to the canvas without a problem.

COMPARISON TO OTHERS / HOW IT WORKS

Linseed oil has faced considerable competition from other oils. Artists have tried many things to spread and fix pigments in a painting. Linseed oil has proven superior to walnut, poppyseed, and safflower oil in improving a painting’s permanence. Additionally, it gives the paint hardness coupled with flexibility.

DEFINITION

Linseed oil never actually dries. It polymerizes and changes into linoxin, a semi-crystalline, very durable yet flexible substance. Most Oils are drying oils rather than polymerizing oils and, therefore, less durable. They get thicker yet are still soluble in Linseed oil. Once dry, it is not easy to dissolve or damage. Linoxin is only mildly affected by many solvents like turpentine, which can be used to thin or clean liquid linseed oil-based paint before it dries. However, there were problems with oil painting. First, it took time to dry—too much time. Also, specific colors were made from substances that would cause a chemical reaction when mixed, turning black or compromising the integrity of the painting. Also, linoxin develops a complex and impervious surface that resists any further layer from bindings or sticking to the underlayer. This can cause upper layers of paint to flake or peel. Different pigments can shrink at different rates when they dry, but if the upper layer shrinks more and is not firmly adhered to the lower layer, the result is a crackled surface. The underpainting is revealed where the upper layer has pulled apart. If the upper layer shrinks less than the under layer, the result can be a corrugated surface. Draper in “The Fall of Icarus” is an example of a crackled surface. The works of Leonardo da Vinci? who continually experimented with oils and mediums, are now self-destructing. Some of his paintings show prominently show the corrugation.

DRYING

The time involved in drying a painting can be an obstacle for artists. Long, dark winters and damp summers in the northern hemisphere make it even more challenging. Classical artists often created underpaintings in egg tempera to speed up the first step of a painting. Some artists today start paintings with acrylic for the same reason. However, there are many ways to speed up the drying process.

Certain pigments like raw umber, Prussian blue, and certain earth greens and metallic copper are great catalysts for shortening drying time. If added in small quantities to slower drying pigments, these pigments can significantly reduce their drying times without vastly changing the color. A grisaille done in raw umber dries very quickly, usually starting to set in less than an hour. Paint layer(s) over dried paint sections also speed up the chemical reaction time, and the upper layer dries faster. It also helps to dry linseed with gentle heat and ventilation. Slow drying is recommended for colors like red and most blacks. Ivory and bone black will dry much faster if a small quantity of pigment, like raw umber, is added to the paint before it is applied. If oils like safflower, walnut, or poppyseed are used, drying can be interminable, extending into days. Several things slow the drying process. Just a few drops of clove oil, which is not available today but was used in the past, would slow the drying considerably, but it would also damage the underpainting if not used very judiciously.

Black (excluding Mars) and red color pigments should be kept in a dark place, cold, or out of the air—all work to halt the drying process. Tubes of paint will keep almost indefinitely if kept in the freezer. Keeping your palette in a closed container in the freezer keeps paint from drying much longer. Before freezing was available, a waterproof palette could be plunged into a bucket of water, and the artist could keep his paints fresh for short periods. Eventually, though, water will gradually affect the oil, causing the surface to go white or cloudy if left too long. You can keep tubes of paint that have lost their tops or have split open in water. It stops them from drying out and makes them usable to the bottom of the tube. You may need to remove a skin of cloudy color on the surface of the exposed paint if left in the water too long.

SPEED UP DRYING

To speed up the drying time, the artists have often used additives, the most common being a varnish/oil/turpentine mixture. The formula was initially used for finishing wood and is still used today. It causes the paint to set, and although it is not dry, it has set enough for a second coat to be applied without mixing the layers. Artists can also use Japanese dryers (siccatives often used to accelerate or catalyze the hardening or drying of oil-based paints) to set their paint. Both methods result in setting the painting. Both have their disadvantages.

- It is much harder to get the topcoat to flow smoothly over the undercoat with a varnish or siccative mixture. The result is that the brush strokes often look chopped or broken.

- Glazes also must be applied with much more liquid, and care must be taken not to show streaks or brush marks. Glazes can also be unstable until they are dry and stay sticky and fragile for a long time.

- The paint surface can become brittle and crazed with cracks.

- Paintings sometimes will turn yellow or crystalize over time and are impossible to correct.

The best way to “dry without damage” with linseed oil is to expose it to UVB light. This ONLY works for linseed oil. Sunlight contains ultraviolet UVB rays. Placing your painting in direct sunlight greatly speeds the drying; most paints need only four or five hours in the sun.

Direct sunlight with nothing between the painting and the light is essential. Glass will block the UVB rays, and screens limit the UVB that can hit the canvas. The history of drying paintings in the sun goes back to at least the Renaissance and Titian, Michelangelo, and Raphael. There are letters between the Renaissance artists sending paintings between Rome and Florence with instructions to leave them out in the sun for a few days to brighten the colors after shipping them; paintings tend to be yellow with storage and age. Paintings during the Renaissance were often created by multiple studios that each specialized in a specific subject like landscape, still life, or figures. Renaissance paintings have endured both in color and paint surface quality better than paintings from more recent periods because of the use of linseed oil.

It is essential to be aware that some pigments, typically organic or fugitive colors, can be bleached if exposed to sunlight. It is essential to check the pigments to verify that they are not light-sensitive before you expose them to sunlight. (on the tube, Myers) Artists like Maxfield Parrish, who were usually on regular deadlines, used sunlight to dry their work. Parrish not only had racks to dry his paintings in his yard, but he also had a room with ultraviolet lights to dry his paintings quickly in the winter or during inclement weather. Sun will not bleach the paints significantly, provided non-fugitive (non-fading colors) are used. Those colors include most earth tones, metal pigments, and some artificial. Fugitive colors are often made of plant dyes. Organic colors such as these will usually fade (???). These colors’ weaknesses will show and either fade or change even without sunlight. Van Gogh, for example, used a lot of chrome yellow, which changed from yellow to green to black…in about three hundred years. It is scary if you have paid $40 million for a family investment. The sunflowers won’t look the same when they fade to shades of gray. This is probably the same reason El Greco’s flesh tones look gray. Many of the reds used then may have been organic and have now faded away.

Some“artist paint” manufacturing companies have a color-fast rating chart. References such as Ralph Meyers’ book The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Technique can be useful hand tools before using a new shade or color.

Artists from the time of da Vinci have tried all kinds of mixtures to dry or improve paint application on canvas and speed the drying process. Some mixtures have extensively damaged or destroyed their paintings. Yellowing and crazing, for example, can be caused by varnish. Varnish may be on a painting as a finish, within the painting as retouch varnish, or even in a painting medium. Varnish can be both hard, Copal, or soft, Damar. Copal, if of poor quality, will darken dramatically. Damar not only yellows but can also crystalize, even to the point that it can be brushed off a painting with your finger. This can be of significant concern if varnish has been used between the layers of a painting. The most common problems are yellowing from age, or a white bloom caused when a painting encounters a lot of humidity. Turner relied heavily on varnished-based mediums. Tate Britain of London has the most extensive collection of Turners, and the conservation department is stumped on how to preserve many of his paintings, which have yellowed to the point of obscuring the beauty and delicate vales of color that are his forte. It would be possible to bleach the paintings in the sun to reverse the yellowing, but the fear of bleaching the pigments within the works keeps the paintings in the dark and continues to yellow because of the medium he chose. The artist Odd Nerdrum has recently seen over 40 of his paintings self-destruct. Jacques Maroger, a well-known artist who developed a medium for painters, saw the folly of his formula and changed some ingredients to correct the problem before he died. American artist Albert Ryder’s paintings still ooze and erupt goo after 150 years on the wall, joining the greats, like Leonardo, who developed painting mediums that have all begun to self-destruct.

DISCOLORING

Yellowing is a problem with varnish, but it is also a problem with all oils. Linseed is no exception. There is a fallacy that linseed oil yellows more than safflower or the other non-polymerizing oils. Because of this belief many manufactures replaced linseed oil with oils like safflower when mulling light colors like white and yellow. Check the contents from manufactures to ensure the paint is made with linseed oil.

The yellowing of linseed oil is accelerated by keeping a painting in the dark. Time will also make oil yellow. To curb yellowing, it is important to use a top quality cold pressed linseed oil. Never use boiled linseed oil. This is in not designed for artists and will yellow to the point of brown. Remember yellowing can be corrected, as long as your colors are not fugitive. By putting the painting in the sun it will not tend to yellow again. It only requires a day or two to solve the problem. If you make your own paints using sun bleach linseed oil, you can also avoid the problem of the pigments fading from sun exposure.

Robert Gamblin of Gamblin Paints, a quality paint manufacturer, has analyzed the problem of oils yellowing. He found that although linseed oil yellows more quickly than the other oils, over time other oils, such as safflower, will yellow more. The advantage of other oils as far as yellowing is only short term. Ironically, Gamblin manufactures Titanium white with safflower as well as linseed oil. Many painters are under the illusion that linseed oil will yellow more than safflower oil and request the latter formula.

To be continued.

Drawing

The choice of medium significantly impacts my drawing style. When I use graphite, my illustrations are intricate and precise, with the added benefit of being easily corrected. Conversely, using ink and colored pencils produces bold and impactful lines. Switching between different mediums allows me to highlight various qualities and strengths in my drawings.

The joy I experience while drawing is undeniable. The challenge of balancing accuracy with freedom, of finding the sweet spot where my vision meets the reality of the page, inspires me greatly. Among all the mediums I use, creating pen-and-ink drawings brings me the most satisfaction, even though they are the most difficult to execute.